Military Barracks in Herford from 1934 until 1937

By Annette Huss

Hammersmith and Wentworth Barracks as seen from the air.

“The second year of nationalist-socialist governance has brought us considerable progress… The most important occurrence for Herford is that the town is now a garrison once again and that the first troops arrived in autumn 1934. At the same time, work has commenced on the new barracks on Vlothoer Straße and Mindener Straße which brought about now employment for many local people and, therefore, the prospect to earn money.”

Since the beginning of the 17th century right up until the second half of the 19th century, Herford had almost always been a garrison town. The only battalion of Infantry Regiment 55 which up until then had been stationed in Herford was moved out in 1867. Regarding the purpose of this location, the Director of Studies Theodor Denecke said in 1939 in his ‘Garrison History’ which he had written upon the Lord Mayor Friedrich Kleim`s request: “Frequent petitions for the garrison to remain here were unsuccessful. Obviously the government ordered for new barracks to be built, and the population in those days with their attitude on humanitarian and political issues neither had the foresight nor the essential selflessness to realise just what the presence of a garrison could mean to a medium sized town like Herford, both for economical and idealistic reasons. Some years later, during 188378 another attempt was made for a garrison to be established at Herford….., but these negotiations, too, failed because of the town’s lack of generosity and leniency”.

The town administrator’s and people’s attitudes had change under the governance of National Socialism. Now, with great administrative and financial effort, there was a willingness to implement the construction of new military barracks. Political and economical motives played a major part in this decision.

The construction of the Herford barracks was an integral part of the plan for the `German population’s ability to defend itself ´and subsequently, also for the national-socialist war preparations. The national-socialist (NS) regime had carried out war-orientated activities from the very beginning. As soon as the end of 1933, Adolph Hitler refused to comply with the armament restrictions as laid down in the Versailles peace treaty. In 1935, he publicly distanced himself from this treaty when he proclaimed armament sovereignty and reintroduced compulsive military service in Germany. “The Four-Year-Plan of 1936…. Set Hitler’s armament process in motion. The objective was to create personnel and material preconditions in support of the intended ‘aggression and expansion policy’ in the shortest possible time. An integral part of the subsequent actions was the definition and development of the military infrastructure. And so, until the outbreak of the Second World War, several new military barracks, airfields and depots were constructed. “Although the German Reich officially abided by the Versailles peace treaty in 1934, in that same year it started to commission new buildings for its future army.

In Herford, too, the foundations for two of the three military barracks were laid in 1934: One anti-tank barracks on Saarstaße, of Mindener Straße (1934/35) and one infantry barracks on Stiftsberg at Vlothoer Straße (1934/35). During 1936/37, another infantry barracks was added at Vlothoer Straße.

The fact that Herford was chosen as a location by the military authorities is down not least to the enthusiasm of the Lord Mayor, Friedrich Kleim who had been in office since 1 August 1933 upon recommendation by his ‘Gauleiter’ (head of a Nazi district) Dr Alfred Meyer. According to Kleim himself, he would much rather have taken the risk of ‘contravening the local finance bylaw’ that expose himself to the risk that the gratuitous provision of property for the construction of barracks would collapse and “the tax authorities of the Reich’s army abandon the construction project and approach another town instead”. It was Kleim who, in the Spring of 1934 conducted negotiations with the responsible district military authorities (Wehrkreisersatzamt VI) in Münster concerning the deployment of troops to Herford. Already on 13 May 1934, the Lord Mayor of Herford concluded an agreement with the Reich’s tax authorities in which the Stadt agreed “to provide the premises required for the construction of barracks at no cost and to make available all supply lines right up to the construction site”. At their meeting on 26 June, Kleim presented the council with a fait accompli. It says in the minute book: “The attendees do not object to the signing of the contract and acceptance of expenses the Stadt would have to bear. They believe that the acceptance of the costs would undoubtedly be outweighed by the potential advantages an existing garrison would bring. Also, to cost sharing in the acquisition of land for the parade ground … there are no objections…..”. The persons in charge obviously expected a strong local economic upsurge, initially through the involvement of Herford businesses and their employees during the construction works and long¬ term because of the troops’ presence. After all, the soldiers would be a not inconsiderable factor to the consumer point of view: “Nobody spends lots of money quicker than a soldier. That is a well-known fact!”

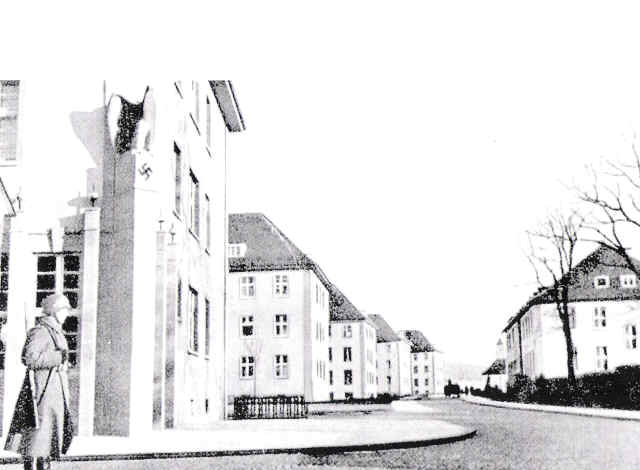

This is a view of the Guard Room at Wentworth Barracks, looking down the main drag, circa. 1937. Blocks A-E can be seen on the left, whilst Block F (used as a hospital) is on the right.

Kleim pointed out this aspect in a letter to Charles ten Brink, a member of the governing body of the clothes manufactory Elsbach in Herford. The company owned terrain that would be a suitable exchange object for the barracks’ construction, but thus far the company had refused to sell for the price the Stadt had offered.

“I am taking the liberty to write to you directly in your capacity as the chairman of the governing body with the request to leave the land to the Stadt for the intended purpose of exchange for the offered amount of 14,000 Reichsmark. I would like to emphasise that in doing so the company Elsbach would do a great service to the Stadt. On the other hand, the deployment of troops to Herford would lead to a not inconsiderable transformation of local structure. At present, the Stadt Herford experiences a distinctly one-sided economic impact. The presence of a strong Garrison would lessen this significantly. I reckon that due to one battalion’s presence alone, the annual sales increase would rise to at least’, 1 Million Reichsmark. The situation would gain a lot more stability which, in the course of time, would also have a noticeable impact on tax burdens. With the provision of said land, Elsbach would render outstanding services for two reasons: Firstly that you would contribute to ensuring a farmer’s continued livelihood which is commensurate with the social-national account of the blood and ground ethos. But also that you would alleviate for the Stadt Herford the set up process for a Garrison.”

Hardly any of the large areas on the outskirts which had, been selected as suitable locations for the construction of barracks by the military building authorities was in the possession of the Stadt at the time the contract was concluded in May 1934. “In partly most difficult negotiations and taking into account dispossession and territory exchange proceedings, purchase the required land was successful at last. The Stadt had to take out a loan for the location on Vlothoer Straße as well as agree to an adversarial exchange with the Stiftberger Mariengemeinde. The military tax authorities made a monetary contribution towards the acquisition of the area at Mindener Straße and in return received municipal properties, amongst them two favoured building plots on Veilchenstraße. At the same time, drawn-out negotiations commenced regarding the purchase of land for a training area and a rifle range. Both were eventually created outside of town in Bischofshagen and Schwarzemoor.” The chronicler of the Schwarzemoor community, usually giving a favourable account of national socialist goings-on, complains in the face of these occurrences: “Now’ Schwarzemoor is affected by the deployment of troops to Herford as well. For the purpose of a large military training area, farmers had to release large” estates on Wetehof No. 2, Laag No. 8 and Rieso No. 6. Near Laag 66, Laag 59 and Wortmann 3b there is going to be a large rifle range for the infantry.”

Although many people welcomed the deployment of troops to Herford, only a few were keen to having to part with their land or even their homes in place of an exchange which was, as a rule, to their detriment. Whoever eventually decided to part with their property after all often did so crying bitter tears, as the widow Marie Hollinderbäumer, whose house on Vlothoer Straße 14 was demolished after vacation, informed the Lord Mayor. The Stadt provided free alternative accommodation for her as well as all the other affected parties and guaranteed remission of fees and charges, tax abatement and mortgages to build new houses.

However, some of the people still refused to sell. In such cases, dispossession proceedings were initiated. Mayor Kleim sees the adoption of the Right of Expropriation as a tactical means with which the land owners might still be moved to come around. “I have justified hopes that once an expropriation order is produced, this will create a basis for negotiations on which an agreement can finally be reached”, he told the military district authorities. These, however, were, more interested in looking after their own interests and replied in short military style: “As far as expropriation should become necessary, it is requested that all documentation concerning these matters is submitted by the aforementioned date. With regards to the property owners, information is required as to why a voluntary release for military purposes is refused. The district military authorities are , not prepared to have to raise costs for their building projects through overtime and night shifts solely due to the fact that the owners are not willing to duly accommodate the military needs of the German people.” This ‘denunciation was followed with the threat of economic sanctions: “The. reasons which inevitably will lead to the enforced utilisation of the required land must be notified to the expropriation authorities so that the validity thereof maybe verified and be taken into consideration upon assessment of compensation. In case of expropriation, unfounded or unsubstantiated rejection by the owners will have an unfavourable influence on reviewing the price level, as was experienced only recently. It is left up to you in what appropriate manner you want to inform the owners in question about this message so that they may be aware of the consequences of their decision.”

There was, however, never an official announcement regarding this kind of “property policy”. “I would like to thank all owners who have left us their property for the construction of barracks, the training area and all other military installations. We as soldiers know what it means to have to relinquish our land. It hurts, it is painful! But there again, everybody has put the German people and the Fatherland to the fore”, praised the then senior Garrison officer, Major Friedrich Karst, on the occasion of the opening ceremony for the first infantry barracks.

The Infantry Barracks on Vlothoer Straße, 1934/35 and 1936/37

Already in October 1934, a training battalion of the Osnabrück Infantry Regiment under the command of Major Karst had moved to Herford “in secrecy”, because during this phase of veiled armed forces amassment, a public breach of the Versailles agreement was yet to come. The Stadt’s corresponding administration report comments: “With regards to the Versailles agreement and the consequential military restrictions placed upon us, we regrettably had to refrain from an official welcome, but from the very beginning troops and population maintained a cordial relationship.”

Construction of the barracks had only begun two months earlier, in August, following the provision of the sites. For this reason, the Stadt provided accommodation for the battalion in the vacant factory buildings Schönfeld on Goebenstraße and Nolting on Hansastraße; these buildings had to be converted specially for this purpose. In the mean time, buildings for the first infantry barracks were erected on the Stiftberg on Vlothoer Straße 37, formerly utilised as agriculturally land As soon as April 1935, the building inspection department reported: “Al11arger buildings’ have either already been made a start on or the general structure is “already completed.”

On 3 October l935 the troop, by now renamed the 1st Battalion of Infantry Regiment No. 58, moved into the finished buildings. “All of Herford was there”, writes the reporter of the Neue Westfälische daily newspaper regarding people’s interest in this event. Still, one can only hazard a guess about how the people’s true feelings. Without doubt, not everybody shared the same enthusiasm. In Herford, too, many people might have thought of the Versailles agreement breach as a deliverance from national “humiliation”. They not only regard the Garrison as a guarantee for a regional economic boom but also as a symbol for Germanic “fortification”. At least that was the expression Major Karst used on the occasion of the ceremonial commissioning of the buildings. Mentioning as an example the collectively achieved (new) construction results, he praised and promoted the unity of people and military, the integration of the “Wehrmacht” into the “people’s community” and the increasing “defence readiness”.

“In all this time they continued to work on these barrack buildings, quietly and diligently, at night time with spot lights, untiringly by day under the blistering sun, construction management, craftsmen and contractors hand in hand with the common aim to give their very best for the strengthening of Germany. They worked in triple shifts and without any breaks, against all odds they all wanted to complete their work by Autumn 1935, and they have done it! At the same time, we do not want to forget that this building project provided many comrades with work and bread on the table, and they have ensured that many contractors and tradesmen are able to continue with their business through these terrible times.

So, people and the military worked in constant unison. They were all connected together non-detachably. I would especially like to thank you, Herr Tillmann, for your commitment and know-how. I am aware of just how hard you have grafted up here and how much trouble you have taken. How often we sat up here together and talked about the arrangements. It was great, though not always easy, the cooperation between construction management and troops but you have always found a solution to ensure that the troops were done justice.”

The government-approved master builder August Tillmann was born in 1904; he worked for the military building authorities in Minden and he had designed the setup consisting of eight accommodation blocks for the ranks and the headquarters and two blocks for offices and service rooms with appropriate annexes. In doing so, he had to follow the given specifications to the letter because “the plans for various barracks in the command area (VI – Münster) were submitted by the building departments of either army, or air force. They were standardised according to branches of the service, checked in Münster and passed on to the respective regional military departments who then had to ensure that the exterior design conformed to the general landscape”. The buildings intended for the ranks, offices and service rooms all had spaced windows, a rectangular outline and hipped roofs with even rows of dormers. Tillmann had decided that these 3- i.e. 2 1/2 -storey main buildings should be rendered above the clinkered plinth. He believed that this design “in their contemporary but unostentatious finish” would reflect ” an….. expressive picture of German industriousness and craftsmanship”.

The arrangement of buildings, as the architect quotes in his specifications, “was decided taking into consideration the strong gradients and true point of compass i.e. direction of sun and general light“. The first four blocks – three for the ranks and the battalion headquarter – Tillmann situated edgeways to the road, one behind the next. The guardroom was situated in a corner next to the main entrance of the barracks and adjacent to the battalion headquarters; it was identifiable by its clinkered outer walls up to door height. Just before this entrance there was – at least until the end of the war – the only hitherto known adornment of these barracks: The sculpture of an eagle, as a national emblem representing the symbol of power and omnipresence of State and Party, sat placed on a tall stele. The architect grouped all other main buildings and annexes around the square parade ground.

The standardisation of the exterior did not stop there but continued inside: In all blocks for enlisted men, a straight corridor separated the rooms opposite each other which received light from the windows from the front face. To both sides of this corridor were the rooms for non-commissioned officers and lower ranks, each occupied by two i.e. six men. Located in the centre was a requisition room (for lectures, armoury and suchlike). At both ends of the corridor were the toilets and washrooms.

When the barracks were taken over, the public was given the chance to take closer look at the buildings. The representatives of the local press also seized this opportunity and enthusiastically reported to the readers in detail everything they had seen. Whether or not they did this of their own volition is a different matter. In any case, their columns trivialised the soldiers presence to a harmless hotel stopover which was interrupted merely by the odd military exercise:

“To say it at the very beginning, our soldiers will without doubt feel very comfortable in their new accommodation here on Stiftsberg. Each room has its own central heating. Once the soldiers have started to arrange their own quarters and so will have added their own note, then surely they will want for nothing more. Obviously, each block has its own washroom so that from the hygiene point of view everything is in the best of order.

In addition to a11 this, this intellectual activities of our soldiers have not been neglected either.They have reading rooms in which undoubtedly it will be a joy to ‘study’. There is also a large lecture room where slides can be shown: This denotes progressiveness and thus will take the extensive training for the members of our forces to a significant new level. In the kitchen, where yesterday we were treated to a tasty soup with bacon and sausage, we admire the huge pots, special ovens for the cooking of fish’ etc….” reports Gustav Röttger from the Herforder Kreisblatt newspaper.

His colleague Georg Heese from the Neue Westfälische newspaper is just as taken with it all: “Walking through the accommodation buildings for the ranks shows that our soldiers after their hard and difficult duties – and it is hard because these days so much more is demanded of them than before – are made really comfortable in their rooms. The hallways are painted in light colours and receive light from both ends of the corridor. Even in the barrack rooms, great importance has been attached to soft and light colours. Each room is occupied by six men, two single beds and two of the usual ‘bunk beds’ with thick straw mattresses invite the weary bones to rest. The lockers are slightly bigger and are divided into more practical sections than before – ‘the comb no longer needs to sit next to the butter’. Compartments for food, writing utensils, cleaning material, underwear and clothes all this is contained in the locker. Everything inside is organised in a soldierly fashion. It is evident that order prevails.

A look inside the shower facilities almost makes one wish to be a soldier again. Once upon a time, these very necessary amenities could be found in dark cellars with low ceilings, there used to be slatted frames on concrete floors, and then a whole platoon at once was stuck under the shower heads. Today, these facilities are on light floors, we can see gleaming shower heads, fitted soap dishes, tiled walls and floors. Of course, these shower rooms are not used on a daily basis for daily cleanliness there are adjacent washrooms, also more than sufficient to take care of everyday hygiene. But when the troops get back after a strenuous march, then the shower room is a most welcome place to freshen up.

In the rooms for non-commissioned officers, one notices a hint of family domesticity. Colourful cushions are scattered on beds, here and there, even a funny little rag doll (who might have given it to the stout-hearted warrior?) on a home-made cushion. At floor level, rifle racks have been fitted into the walls. Furthermore, a large lecture room with a screen deserves total admiration. Nowadays, ‘the most modern acquisitions are put into service for military instruction.

Then we take a quick look at the stables which present the expected picture of cleanliness and good order. Each horse has its own drinking trough so that water no longer needs to be taken to the arumals. An indoor riding school provides an facilities for tournaments, and the riding area which is being constructed outside offers plenty of space for exercising the horses.

Lastly, we take a look into the kitchen where we can see three huge steam-heated pots (for vegetable, soup and potatoes), an enormous gas cooker for anything fried and a large fish-frying facility which all take care of the empty stomachs. Adjacent to the kitchen are dining halls for the ranks and non-commissioned officers; there are no stools but proper chairs and tables covered with linoleum. So the guests walked through the large buildings right up into the attics which, as always, are reserved for individual purposes. The unanimous verdict was: The barracks in Herford are exemplary!

The buildings had hardly been occupied when Lord Mayor Kleim entered new negotiations with the military administration authorities in Münster because of a “final statement regarding the previously chosen land for a third barracks”. Due to a change in legislation, this time the land was purchased by the government tax authorities. However, the land for the officers’ mess annex was once again provided by the town, free of charge. The “new development for an infantry barracks, an officers’ mess and a technical training centre” commenced in September 1936, opposite the first infantry barracks on land between Vlothoer-, Stadtholz- and Ulmenstraße and received street number Vlothoer Straße 40.

This second barrack complex clearly showed, more than the first, exactly what the Wehrmacht expected their buildings to look like: The architecture must be “uncomplicated”, “soldierly simplistic” but at the same time presentable as befitting the military position in a national-social state. The blueprint for the second infantry barracks came from the architect Dr. August Jost, born in 1900 and also working for the military building department in Minden. He supervised the construction of five accommodation blocks for the ranks and two buildings for offices and service rooms as well as the annexes.

Here, too, rectangular and 3 storey, buildings with hipped roofs and dormers emerged with winged mullion windows and doubled up doors, arranged edgeways towards the road, but a different picture nonetheless: The buildings in the second infantry barracks appear to be unequally massive, statelier than the neighbouring ones in the first barracks. This reason for this was the use of green natural stones which are “bordering” the otherwise rendered buildings. All building edges, including those of the protruding staircases which make the appearance less severe, show this green natural, stone. Because of this, the buildings gained more contours whereby the large stone cuboids conveyed “steadfastness” whilst the building looks solidly constructed at the same time.

The headquarters, located again right next to the main entrance, deserves a special mention for the cladding of the integrated guardroom: The relevant outer walls around the high, narrow windows were completely cladded with green stone, the pilasters in between the windows crowned with an orb. On a pillar at the corner of the building stood the familiar eagle again as the national emblem.

On 7 October 1937, two short-training battalions from Infantry Regiment No. 58 moved into the buildings which by contemporaries were described as “nice” and “friendly”, although “the earthworks” all around were “not quite finished”.

At this time, the officers’ mess which was separated from the second Infantry barracks by the new road Von-Kluck-Straße (today Liststraße) was still under construction.

The plans for this Z-storey building with a noticeably high hipped roof were drafted again by August Jost who obviously had been inspired by various gothic examples. Joined to each sides of the protruding rectangular main building are low wings. The entrances to the building are located in these wings; above the one on the left-hand side parades an ornamental stone. It was put up in 1937, the year construction commenced, and depicts the town’s landmark: A reared-up horse. The window pattern repeats the design element of the accommodation blocks for the ranks on the opposite side of the road. Whilst this building facing the roadside comes across as rather austere and mysterious, the garden side in contrast presents itself as light and elegant with its integrated rotunda, arches and end-to-end narrow windows.

“Unostentatious”, “contemporary”, “fortified” and at the same time aesthetically superior: This is how the Infantry Barracks on Vlothoer Straße precisely, met the expectations of their contractors who with these buildings intended to reflect the power of the Wehrmacht (and also its significance within the national-social state). “The soul of the soldier and the spirit of the troops, these are the superior components in military architecture; the constructor must experience them in order for them to have the desired effect We expect military buildings to express the plainness of the soldier. Not primitivism, but a healthy simplicity which consciously and stoutly reflect their personal values …..We want our buildings, the ground plans and facades designed with a crystalline clearness; we expect exemplary craftsmanship, solid building materials .and a decent attitude which respects the nation’s concerns for the building trade with dignity.”

Exucursus: Vlothoer Straße 16 – Der “Storksche Kotten” (Stork’s Cottage)

The construction of the second Infantry Barracks was preceded by the demolition of 4 residential houses on the premises: Vlothoer Str. 14, 16, 44 and 46. The Stadt had bought the buildings previously so that they could be demolished as so on as the civil works made it necessary. House No. 16 was a grand half-timbered farmhouse in the Ravensberg style, the so-called “Storksche Kotten”. The administrative district made their interest in this house known and requested the Stadt to leave it to them for dismantling free of charge so that it could be reconstructed on the Amtsberg in Vlotho as a hostel for the Hitler youth. In a letter to the district councils, Lord Mayor Kleim put forward arguments for this solution: „Although the timber in this house might be of considerable value which might have prompted the district to meet the asking price for this property, I still believe it to be justified to refrain from doing so. The idea of not to destroy this cottage built in the Lower Saxony farmhouse style should be embraced whole-heartedly, so that it can be rebuild in its original state and thus ensure its existence for many more years. Considering that the owner is a public corporation, the time-frame can be extended much longer as opposed to a private person taking over the construction works. An additional point is that the house is intended to be commissioned for future use by the youth. For all these reasons, I believe it to be best to comply with the district’s wishes and to leave them the house at no charge. Bearing in mind the strong connection between Stadt and district, the present situation is one that ought not to be decided merely on a financial basis.

At least, the district accepted the expenses for a “nonrecurring relocation” for both families still living in the house: ” … that is to say that the families will have to move twice because their intended ultimate dwelling in the new housing residence has not been finished yet. The costs for this move will be borne by the government tax authorities.

During 1937/38 and “after elaborate renovation”, the cottage was rebuild in Vlotho as a “Bannführerschule” (youth training centre?) for the “Hitler Youth”. The centre received the historical name “Herzog Widukind”. It was supposed to emphasise the “bond with the soil”.

Since the end of the war the building, in the meantime renamed “Jugendhof Vlotho” (youth centre), serves as a centre for democratic youth education.

Addendum

In July 1938, Herford hosted the celebrations for the 125th anniversary of the “17th”. This infantry regiment, named “Count Barefoot” after their first commander, used to be stationed in Herford during the First World War. On the occasion of this anniversary, Regiment 58 assumed their traditions, in actual fact they took over the historical traditions of this unit from the old army.

By fostering these traditions, it was intended to strengthen each soldier’s ties to their respective formation and to instil pride in their “status”. Simultaneously, they as “conspiratorial fellowship” were to make their own those traditions such as loyal following and readiness to make sacrifices – until death. With each passing on of these traditions, historical continuity was cemented which the new army incorporated into the state and “ennobled” at the same time. For this occasion, the barracks on Stiftsberg had set up a so-called “tradition room”. On view together with some mortars was the bell tree donated by Grand Duke Ludwig III of Hesse, commander of the Regiment from 1843 – 1847; there was also a tablet denoting a11 the battles the “17th” had fought. Also, both infantry barracks which up until then had not been given names received “in honour of the Commanders of Infantry Regiment 17” the names “Estorff-Kaserne” and “Stobbe-Kaserne”. Major General von Estorff had been the regiment’s last peacetime commander; Major General Stobbe was the last wartime commander. Stobbe persona11y attended the anniversary celebrations.

On 27 August 1939, just before the outbreak of the Second World War, “the active troops left the location; the Regiment was under the command of Oberst (LI. Col.) Windeck who had taken over from Oberst von Döhren in January 1937. Through the release of an active core unit and replenishing with reservists, a new 2nd wave regiment was assembled. Named Infantry Regiment 216, it left the location only a few days later under the command of Oberst Karst. During the war, the new recruits did their military training in those barracks.

On 2 April 1945 and “by order of Major General Karst……the last soldiers remaining in these barracks on Stiftsberg were taken by lorry and bus to Horn in order to reinforce the 466th division fighting under his command”. All food rations left behind in the barracks were distributed amongst the population of Herford; this was to ensure that nothing would fall into the hands of the advancing American troops who subsequently occupied the town on 4 April. Because Herford belonged to the British occupation zone and the British military government had made Herford their “Control Commission for Germany” (CCG), it was the British military forces that moved into both barracks on Vlothoer Straße.

Now known as “Hammersmith” and “Wentworth” barracks these grounds, in most part unchanged, are still being used by the British military. However, all buildings underwent minor fittings, conversions and extensions in order to accommodate requirements. (Parts of the interior decoration, had already been destroyed immediately after the end of the war.) The annex buildings had wider doors fitted and windows were replaced with glass bricks. The offices and service room buildings had extensions built. In Hammersmith Barracks, part of the stables was converted to become the Garrison church. Wentworth Barracks has a cinema since the 1950’s. A new administration building was erected as was a school for the children of the British forces members; one of the former offices and service room buildings forms part of the school. One of the former accommodation blocks for enlisted men now houses a radio station of the “British Forces Broadcasting Service” (BFBS). (since the beginning of the 90’s). The Officers’ Mess, too, received an extension.

The most noticeable change in both barracks has to be the new yellow-green paintwork of the main buildings. In addition, the front sides of 2011 accommodation blocks were recently fitted with metal spiral staircases – the so-called exterior escape stairs – as a means of escape route in case of a fire. In order to enable access to these, door openings had to be knocked into the walls; the relevant window openings were made wider, too. Finally, the enclosures around the barracks, originally just high metal fences in between stone pillars, were reinforced to the point of insuperableness for the protection against IRA attacks. This gives the barracks, now surrounded by residential houses, an even more ‘odd’ appearance.

The above is a translation of the essay “Die Kasernenbauten in Herford 1934 bis 1937”, which has been published for the first time in the “Historisches Jahrbuch für den Kreis Herford (Historical Yearbook for the administrative district of Herford) 1999”, p. 103 -127, where one can find the footnotes missing in the translation.

Annette Huss