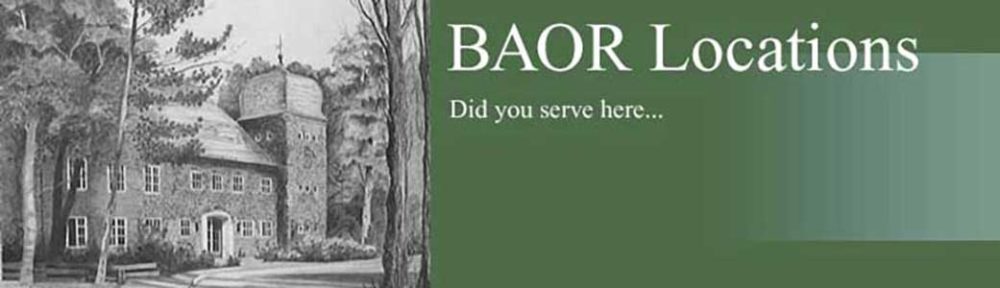

Although not a British prison, this prison was manned by British troops for 1/4 of each year (Jan, May & Sep – the other 3/4 being shared amongst the Americans, French and Soviets). Each guard was manned at platoon strenght of 1 officer and 37 other ranks, supplimented by 18 warders. The prison had 6 watch towers in which to monitor the prisoners, with the Soviets using this to their advantage as Smuts Barracks was next door to the prison.

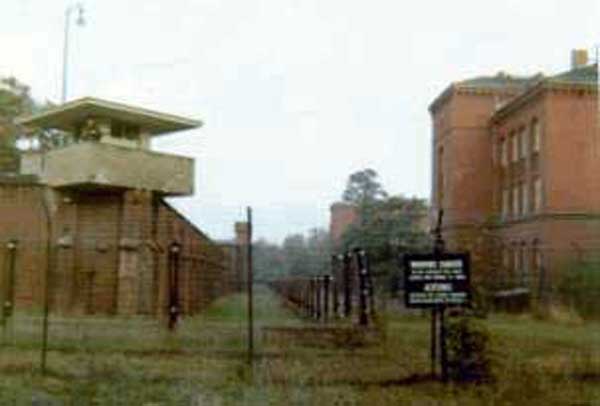

The prison itself was built in 1876 for use as a military prison, but it was decided upon, after the Second World War, to be used to house seven Nazi war criminals (the prison had held 600 people at one point, so you can imagine the room they had). They arrived on 18 July 1947, with the last one leaving (by means of a coffin) on 17 August 1987. This last one being the infamous Rudolf Hess, who had committed suicide after being the solitary remaining prisoner since 1966. After his suicide, the prison was demolished to prevent it becoming a magnet for neo-Nazis. The rubble was then dumped in the North Sea. For more in depth information on Spandau Prison, please click here.

Rudolph Hess taking exercise

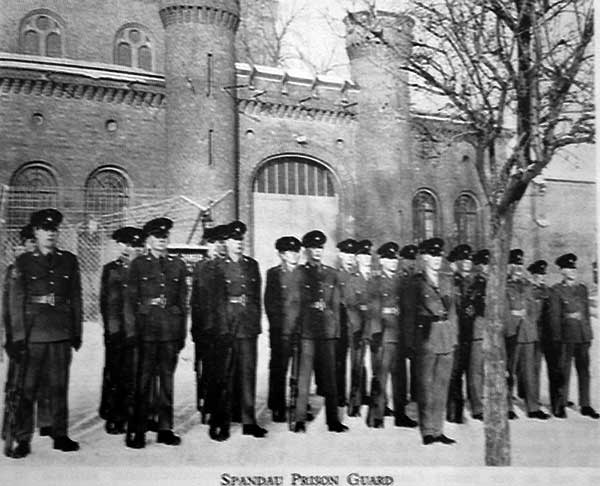

Perimeter wall. The paths that you can see were trodden by the loneliest man on the planet.

Perimeter wall

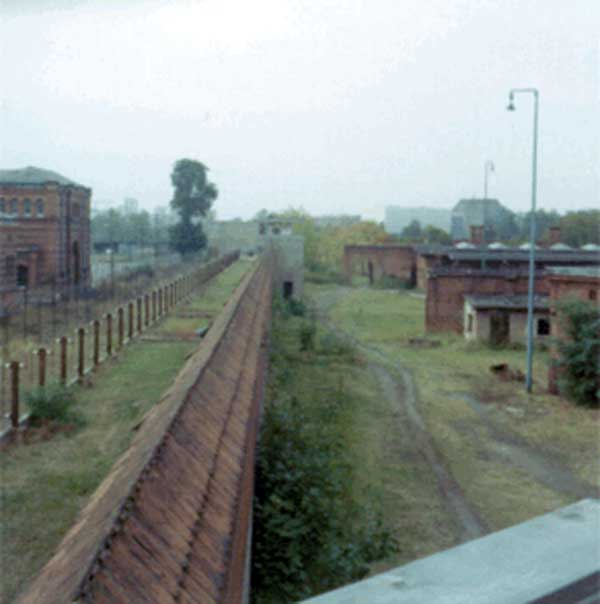

One of the 6 watch towers being manned by British troops

This appears to be where Spandau Prison meets Smuts Barracks

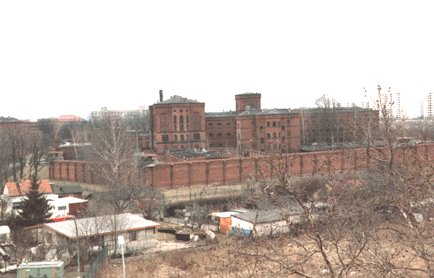

Spandau Prison, viewed from Brooke Barracks. As you can see from this picture, it was quite a sizeable space for 7 men.

Courtesy of Mr Andrew Kaye.

Prisoner at Spandau a double?

According to Dr. Hugh Thomas’ book The Murder of Rudolf Hess (1979), the prisoner tried at Nuremberg and incarcerated in Spandau as Rudolf Hess was actually a double who was willingly impersonating him. Dr. Thomas examined the prisoner in 1973 whilst serving at BMH Berlin and writes that the man had no scarring that would indicate a bullet wound whatsoever. The real Hess was shot through the left lung, the bullet entering just above the left armpit and exiting between the spine and left shoulder blade during World War I. This finding appeared to be confirmed when the prisoner’s body was given two separate autopsies after his death in 1987 neither of which reported finding scarring that would indicate such a wound; however, when Hess’s full medical records were released it was revealed that the bullet wound was in a different place than Thomas had claimed, and that scarring from the clean shot was likely to have been minimal.