On first arriving in Germany, I didn’t really give much thought as to the make up of the barracks or the history behind them. It was only later that I decided to look more in detail. Soon, similarities started to crop up in their design such as the emphasis in symmetry. This occurred to me to be normal as a member of the military; as everything should appear to be in order.

The origins of these Kasernen (camps) stem back to the 1930s. With Germany building up its armed forces, they also needed somewhere for them to be stationed. This led to the majority being completed during the period of 1935-36. It also helped ease unemployment; just as somebody had to live in them, somebody had to build them.

Where troops were to be accommodated (MB – Mannschafts Barracke), a square would be formed with the end block usually being a headquarters or utility block (WB – Werkschafts Barracke). These would often be in the form of cookhouses. For me, it meant better quality food rather than the impersonal, conveyor belt system of mass feeding that we employ now. Good examples of this can be found at Fallingbostel and Hohne. A parade ground would then usually feature in the middle of this square (Fig 1).

Figure 1 – Showing the symmetrical arrangement of Northampton Barracks, Wolfenbüttel.

For the MB blocks the living area tended to be on three floors. The floors would be split in two halves with two sections in each. The troops would then share communal rooms with the section commander having a single bunk. There would also be an attic and cellar. The cellars would be used not only for storage, but also as shelters (Luftschutz bunker) for when the allies strafed or bombed the camps. Examples of this can still be found on the walls at Mansergh Barracks, Guterslöh, where the words Zu Schutzraum (Fig 2) are still visible. To reduce the chance of injury, screens were built externally from brick around the windows offering limited light, but protection from shell splinters (Fig 3).

Figure 2 – Mansergh Barracks still displays these artefacts of Hitler’s Third Reich.

Figure 3 – These brick shields tend to have been removed by the British for obvious reasons, however these remain to this day at Elizabeth Barracks, Minden.

On entering the attic another bunker (Fig 4) would be found. These were used by the fire sentries to give advance warning – should the building start to burn. The sentry was also expected to fight fires, removing the incendiaries that crashed through roofs and into attics before a blaze could take hold. Also in the attic, vast amounts of sand would be laid evenly throughout the entire floor space, extinguishing the fire once it had raged enough for the ceiling to collapse.

Figure 4 – This brick shelter which sits within Catterick Barracks was designed to give those on fire watch the ability to shelter from bomb fragments and the odd round that was fired trying to darken the search lights.

Figures 5 – These ladders would lead to a window in the roof through which burning buildings could be observed and acted upon. The height of the blocks in Mossbank/Rochdale Barracks (or any for that matter) would give reasonable visibility when compared to the local surroundings.

The quality of the accommodation is also seldom appreciated except by our former National Servicemen. The windows were double glazed, beach floors, marble window sills and solid oak banister rails. These privileges were not only limited to the officers mess. It came as standard. Another quality was the size of the corridors (Fig 6). Should a parade need to be held indoors for whatever reason, there is no reason why it couldn’t be. These were after all designed for a Thousand Year Reich.

Figures 6 and 7. This corridor belonging to Mossbank/Rochdale Barracks still has many of the fittings that were present on the completion of the barracks. These include the doors, radiators and gun racks.

The architecture used by different arms of the services are quite easily identifiable. The Luftwaffe under Goering would add flair using domes (Fig 9). Whereas Das Heer (the Army) tended to prefer rectangular shapes. Still, each camp although following the same pattern would differ slightly by the style of brick work or clock tower featured. Another alternative would be to plaster over the brick and paint it Prussian Yellow.

Figure 8 – Many of the Luftwaffe camps were actually built as Flak Kasernen, being placed at strategic points within the cities. The image above shows a typical search light and a static mounted 12.8 cm Flak 40. Apart from cork screwing, the RAF’s other method of preventing the search light from locking effectively onto an aeroplane would be to fire straight down the beam of light with their .303in machine guns.

Figure 9 – Hobart Barracks, Detmold. There would be many turning in their graves should they ever find out the state of these barracks. What was a busy camp is now a play ground for vandals.

For the officers which were quartered on camp, each type of accommodation would be prefixed appropriately to that rank of officer. Many of the quarters in Fallingbostel and Hohne are still designated so to this day and can be identified by the following:

L – Leutnant/Lieutenant

H – Hauptmann/Captain

S – Stabsoffizier/Staff Officers (Oberstleutnant/ Lieutenant Colonel and above)

G – General/General

BG – General’s Staff

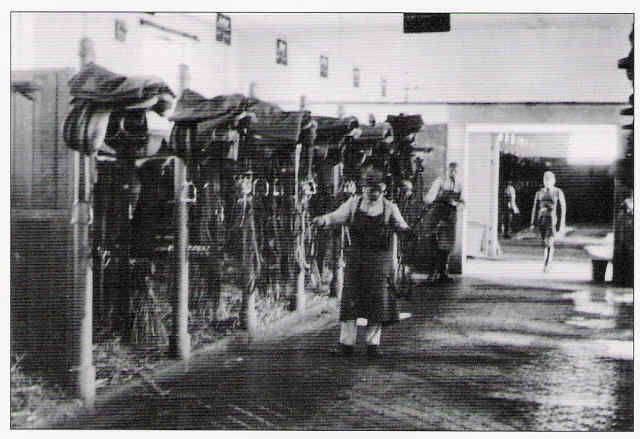

Figure 10 – A typical German Army stables, this one being at Fallingbostel. What is often overlooked is how dependant the German Army was on horses. The infantry regiment was fully horse drawn with exception to the machine-gun company of each battalion. All the rear services were (butchery, bakery, post, ammunition etc) were reliant on horse drawn wagons. When the German Army marched into Russia, they were in reality not faster than that of a Roman Legion nearly two thousand years earlier. To put this into perspective, over 700,000 horses crossed the Russian border, but only a few thousand tanks.

Figure 11 – Clifton Barracks, Minden. These are the last of the stables still to be standing. This one in particular was used as the workshop bar.

Figure 12

Abbreviated as ST – Stall, stables would feature in every camp and so would a Reit Halle (riding hall). This was due to the German reliance on horses. The majority of the riding halls were converted into gymnasiums on our acquisition of the camps. Metal tethering rings (Fig. 12) can still be found externally on many of the buildings. Fallingbostel is a good example of the German dependence on our equestrian friend, with one complete side of the camp is lined with what once were stables.

Whilst we are in the general direction of the tank park. I would like to touch on the subject of cobbles. These were not as common as they were because a German field marshal had visited northern England and liked what he saw. They were used because of their ruggedness when it came to panzers being neutral turned all day long. It is another example of things being built to last.

Last, but not least; pomp. The Germans loved pomp (Fig 13) and used it for what it was – to inform their soldiers that they were part of something big. It gave an aura that they were the greatest army of their time (which arguably they were), but it also stated authority. These imposing Offizier Casinen, effigies and flags were used to their maximum.

Figure 13 – BMH Münster. The quality of this building radiates an impression of being part of something great and also gives the viewer a feeling of being in safe hands.

For more information on the naming of barracks, please click here.